What We Endure

And what it means for our lives

My teaching career, such as it was, began in 1996 in Mendoza, Argentina—a high school English class in the morning, a college course on translation in the afternoon, and private English classes in the evenings. It ended in 2021 when I turned 50, after I left a “temporary” adjunct lecturer position at Cal Poly that I’d held for nearly 17 years.

In between Mendoza and Cal Poly were substitute teaching gigs, including a stint for the San Luis Obispo school district where I tutored students who were not well enough to attend school or who had been expelled. One of the “unwell” students attended SLO High; I think she was a sophomore or junior. I was her tutor because she’d been drugged and raped at a party, and when she came to, she was pregnant with twins. I’m not sure if she began staying home from school when her pregnancy progressed to a certain point because she could not sit comfortably at the classroom desks anymore—her belly was quite large by the time I started tutoring her—or if she just wanted to remain out of sight until she gave birth. I think of the Spanish word for pregnant, embarazada, which sounds like “embarrassed.” Looking up the word in the Spanish/English dictionary my pal Al gave me when I lived in Argentina, I see the that the word for pregnancy, embarazo, is first translated as “obstacle, impediment, difficulty, interference, obstruction”—and only secondly as pregnancy. The third translation is “shyness, bashfulness, embarrassment, awkwardness.” How awkward to be pregnant with twins in high school.

She lived with her very religious grandmother—I think her mother also lived there, but I can’t remember. There were crosses of various sizes and styles hanging in the hallway and in the dining room where we sat for lessons. She said they had figured out who the perpetrator was but didn’t press charges. I pride myself on being a good teacher—I strive to make my students comfortable, to make them laugh, to make them feel heard and understood. This girl, she made herself impenetrable. I had never spent so much time with someone so visibly angry. She did her work without speaking or replied only in monosyllables. The last time I saw her was after she’d given birth. She showed me a photo of her in the hospital, her newborn twin girls in her arms. They were adopted to a very stoked local couple. She smiled when she showed me photograph—the only time I saw her smile—a mix of pride and what must have been relief. I never saw her again, though I always wondered what happened to her. I may have even written about her before here—I’m not sure. She’s often crosses my mind.

I hope it isn’t a breach of privacy to talk about her; that’s certainly not my intention. I just think that to be a girl, to be a woman, has its own unique vulnerabilities. Women are incredible, what we can endure. But we don’t always prevail. I wonder: Did the girl prevail?

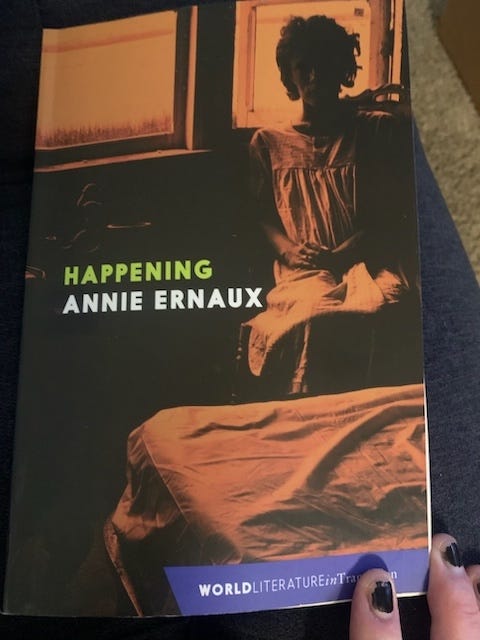

In my book group—a group I’ve been lucky to be part of for many years—we recently discussed my picks, two 96-page books by Annie Ernaux, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2022: A Man’s Place, about Ernaux’s father, and Happening, about the author’s illegal abortion in France in the 1960s. Happening was made into a film I reviewed here. I hadn’t read the book when I saw the film. Sometimes seeing a film first can ruin the book or vice versa. Not so in this case.

Instead of a writing a review or synopsis, I’m putting down my favorite passages from the book here in chronological order. To me, these excerpts provide something more than a summary; they almost feel like a narrative poem. There was some debate among my book group whether this was memoir or fiction and whether it matters. The back of my paperback copy says it is memoir, but inside on the copyright page, it is listed as fiction. I think it’s interesting how how our expectations change depending on the genre. For one of the book group members, this worked as a memoir but not necessarily as a novel, for instance. For me, it just worked. A friend in my book group texted me this photo and message when she finished the book: “This book wrecked me.”

I took that to mean it worked for her too.

As someone who’s written both fiction and memoir, I appreciate the crossover. Ernaux wrote this book 40 years after the “event,” drawing from memory, which she knows is sometimes unreliable, and diary entries. She doesn’t try to adorn her prose; she’s not trying to entertain the reader; in fact, in A Man’s Place, she wrote: “Naturally I experience no joy in writing this book,” a sentiment—or lack of sentiment—that likely applied to the writing of Happening too. And yet, she’s compelled to tell these stories, to find meaning yet not infuse meaning. In other words, her work is very French!

To give some context: Basically, the narrator (Ernaux herself) is a first generation college student. She’s a young woman from a working class family who is attending university and studying literature in hopes of becoming a teacher. She becomes pregnant and wants to have an abortion, but abortion is illegal. Her desperation to have the abortion is palpable throughout the slim, fraught book. I’ve shortened some of the excerpts with ellipses. The parentheses are hers.

The law was everywhere….In the sheer impossibility of ever imagining that one day women might be able to abort freely. As was often the case, you couldn’t tell whether abortion was banned because it was wrong or wrong because it was banned. People judged according to the law, they didn’t judge the law (35)

Now these “intellectual heavens” were out of reach: I was wallowing down below, my body overcome by nausea….In a strange way, my inability to write my thesis was far more alarming than my need to abort. It was the unmistakable sign of my silent downfall. (My diary read: “I can’t write. I can’t work. Is there any way out of this mess?”) I had stopped being an “intellectual.” I don’t know whether this feeling is widespread. It causes indescribable pain (38).

(I realize that this account may exasperate or repel some readers; it may also be branded as distasteful. I believe that any experience, whatever its nature, has the inalienable right to be chronicled. There is no such thing as a lesser truth. Moreover, if I failed to go through with this undertaking, I would be guilty of silencing the lives of women and condoning a world governed by male supremacy) (44).

I was the sort of girl who went with the flow (55)

I was convinced I had to push back my own limits and reach the top of the mountain to get rid of it. I wore myself out trying to kill it under me (55).

(…I have no idea which words will come to me. I have no idea where my writing will take me. I would like to stall this moment and remain in a state of expectancy. Maybe I’m afraid that the act of writing will shatter this vision, just like sexual fantasies fade as soon as we have climaxed) (57).

I was standing by the bed, facing a woman with a swollen complexion, who spoke fast, with quick, jumpy movements. This was the woman to whom I would surrender my insides, this was where it would all happen (59).

(To experience anew the emotions I felt back then is quite impossible. The closest I can get to the state of terror thrust upon me that week is to pick out any hostile, harsh-looking woman in her sixties waiting in line at the supermarket or the post office and to imagine that she is going to rummage around in my loins with some foreign object) (61).

I feel that the woman who is busying herself between my legs, inserting the speculum, is giving birth to me. At that point I killed my own mother inside me (63).

When Jean T, LB and JB all came to see me together, I told them about the hemorrhage and my grueling reception at the hospital. A light-hearted narrative which they thoroughly enjoyed and which carefully omitted the details they were to haunt me thereafter (83).

I would listen to Bach’s Passion According to St John in my room. When the Evangelical’s solo voice rang out in German to celebrate the Passion of Christ, I felt the ordeal I had suffered between October and January was being re-counted in an unknown language… the probe and all the blood all became engulfed in the misery of the world and eternal death. I felt saved (87).

On another afternoon I entered Saint Patrice’s Church just off the Boulevard de la Marne to tell a priest that I’d had an abortion. I immediately realized this was a mistake. I felt bathed in a halo of light and for him I was a criminal. Leaving the church, I realized that I was through with religion (88).

Now I know this ordeal and this sacrifice were necessary for me to want to have children. To accept the turmoil of reproduction inside my body and, in turn, to let the coming generations pass through me (91).

Happening ends with these words:

Maybe the true purpose of my life is for my body, my sensations and my thoughts to become writing, in other words, something intelligible and universal, causing my existence to merge into the lives and heads of other people (91-92).

The things that made this so relevant and real for me: Her drive to escape a childhood of working class poverty; her passion for literature and writing; her sexuality, for which she doesn’t apologize. Like Ernaux, I’ve kept diaries since my girlhood. And, also like Ernaux, I aborted, was the first in my family to finish college, became a teacher, and eventually, a writer and mother.

Thank you, Annie Ernaux. Your existence certainly merged into my life and my head.

And thank you for reading.

P.S. My editor is on “sabbatical” (working his job by day and laying back patio pavers at night or practicing music) ; the tangents and typos are all mine!

Thank you for this. Ate it up. Storytelling in community lightens the heaviness.